Ghana's Gold Curse and Extractive Mechanisms in Neocolonialism

“They do not use tanks; they use banks.”

When Ghana’s president warned of this new form of colonialism in 1965, he was speaking about sovereignty, but today his words surface in a far more basic struggle: clean water. The Gold Coast of Ghana faces the need to import drinking water, as rivers are poisoned by gold mining. This looming water crisis is not an environmental accident. It is the visible endpoint of decades of debt-driven development that turns natural wealth into external profit, while leaving societies with the costs.

The curse of natural resources – the phenomenon that resource-rich countries exhibit weaker economic performance than those with fewer resources – is paradoxical.[1] Economists also call it the “Dutch Disease,” a term coined in 1977 to describe how resource booms can appreciate a country’s currency and divert labor and capital away from manufacturing and agriculture, ultimately undermining economic performance despite increased resource wealth. The oil dependency of Venezuela’s economy and the oil price collapse in the 1980s and 2014 is often cited as an example of such dynamics.

Economists such as James A. Robinson challenge the idea that resource wealth automatically leads to decline, emphasizing that the governing institutions and political incentives are decisive. In systems dominated by extractive institutions, resource revenues tend to be monopolized and used for short-term purposes, while under inclusive institutions, the same resource wealth can instead support sustainable and broad-based growth.

From Colonial Rule to Financial Dependence

The prime historical example for extractive governance is colonialism. Colonial powers extracted resources and revenues from colonies actively preventing the formation of a diversified domestic economy. But after decades of political independence, development programs, and foreign aid, why do so many resource-rich countries still remain poor?

Political independence, although being an important step, did not create full sovereignty. Instead, control shifted from overt imperial domination to financial mechanisms. This transition was articulated early by Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, who warned that political independence without economic autonomy is ultimately meaningless. In his 1965 work “Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism”, Nkrumah observed: “They do not use tanks; they use banks.”[2] His thesis was that external control, and extraction now operates through debt, trade dependency, and international financial institutions rather than direct military occupation.

“The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality, its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.“

Kwame Nkrumah, 1st president of Ghana 1960 – 1966.

Known to the British Empire as the “Gold Coast Colony” because of its abundant gold, Ghana gained independence in 1957 under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah. Ghana’s independence was initially regarded as a development success story. However, during the struggle for independence, Nkrumah rejected financial programs proposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), viewing them as threats to economic sovereignty, and relations with the United States deteriorated rapidly. [3] One year after the publication of his book, he was overthrown in a military coup in 1966, an event later acknowledged by former CIA officials to have involved US intelligence.[4] The subsequent military government of Ghana rapidly adopted IMF and World Bank programs.

The Model of credit-based development

The IMF and the World Bank were established in 1944 as core institutions of the Bretton Woods system, with the stated aim of promoting global financial stability and postwar economic reconstruction. When the decolonization process started on the African continent, IMF & World Bank expanded to longer-term financing for developing countries (Egypt 1962, Morocco 1963, Tunisia 1964, Algeria 1966 and to the newly free states of Ghana 1966 and Kenya 1967) claiming to promote economic development. Credit-based development is commonly understood to work via the following process. Loans are used to finance infrastructure development, stimulate export growth, and raise state revenues, which can subsequently be used to service the debt, foster prosperity and lead to economic independence (Fig. 1).

Fig 1: An ideal model of the effects of credit-based development aid.

In practice, credit-based development as implemented by the IMF and the World Bank has produced different outcomes. After decades of credit-based development aid, most developing countries remain at early stages of economic development while also facing persistent and often unsustainable debt. [5, 6]

So where does the development-loan mechanism go wrong?

-

As loans are typically denominated in foreign Dollars, recipient countries assume significant exchange-rate risk, making debt servicing more expensive when domestic currencies depreciate. It is noteworthy that the IMF made political exceptions here. Under the 1953 Agreement on German External Debts, West-Germany was allowed to service its obligations in its national currency. [7]

-

Repayment is expected to be financed through export earnings, which in many developing economies are based on raw materials or agricultural commodities and their global price volatility (see Venezuela’s oil crashes in the 1980s and 2014). And as these primary commodities generate far less export revenue than higher value-added goods along the value chain, developing countries often become reliant on new loans to service existing debt.

-

New loans are not unconditional. Funding would be provided only if the recipient country committed to IMF demands like reducing its budget deficits or conduct “structural adjustments”. Structural adjustment programs (SAPs) prioritized external balance and debt servicing over domestic development. SAPs reinforced specialization in raw material production while limiting diversification. This redirection toward export infrastructure perpetuated the dependence on volatile commodity exports.

-

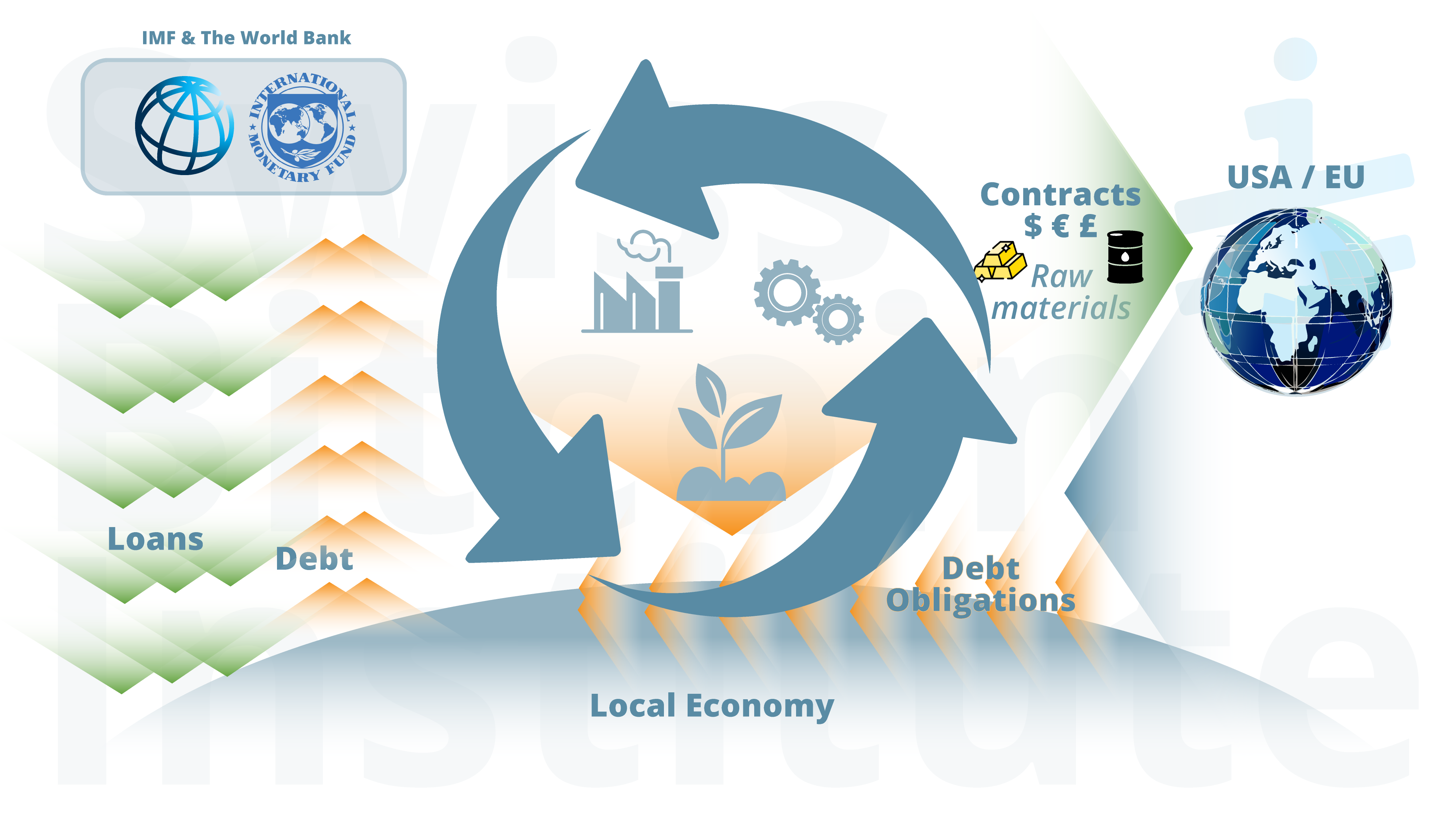

Another common appearance by IMF- and World Bank-supported development lending is the so-called “double loan”, in which external financing nominally given to developing countries is partially cycled back to companies from creditor states. Loans were often tied to procurement requirements that awarded contracts to foreign companies, enabling them to capture profits immediately while the recipient country retained the full debt burden. Half the contract value of World Bank-funded projects in the last decade went to companies from creditor states.[8]

As a result of 1-4, development loans effectively subsidized foreign corporations, while the recipient country carried long-term foreign-currency debt, increasing external dependence without building a diversified domestic industry (Fig. 2).

Fig 2: The extractive mechanism of credit-based development: Foreign currency credit dependence, primary commodity focus and double loans.

The debt trap

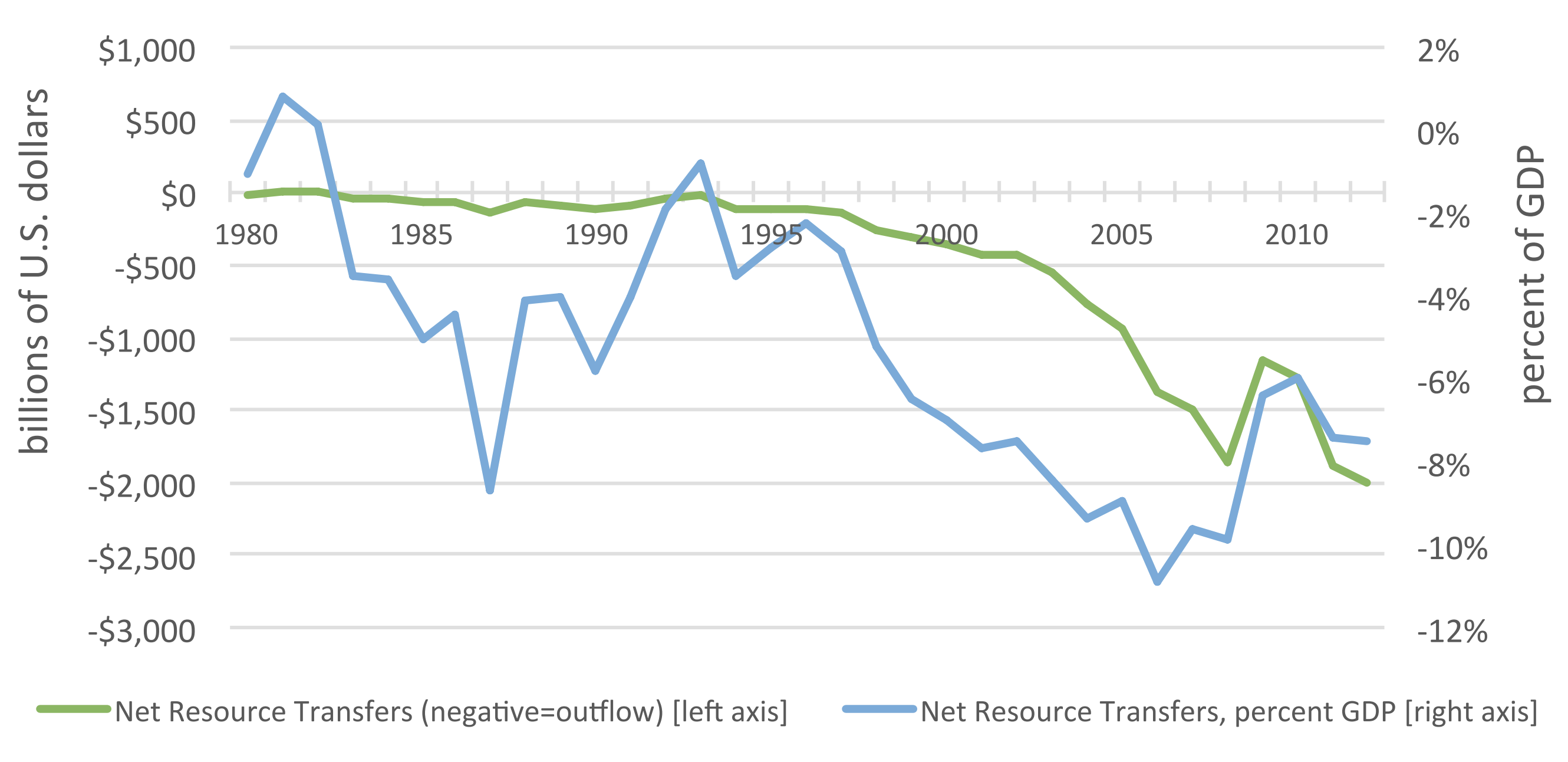

Most developing countries began accumulating foreign debt in the 1960s, and over the following two decades this debt evolved into a structural mechanism of capital outflows. 1982 was the year in which rising interest burdens reversed global capital flows: since then, net capital flows each year from poorer countries to richer ones (Fig. 3). [9]

Today, net capital over a trillion dollars per year flow from the Global South to the Global North. [10] For every dollar of aid received, developing countries lose roughly twenty-four dollars through net financial outflows. [11] Persistent net outflows of this magnitude place developing economies at a significant structural disadvantage.

Fig 3: Net Resource Transfers from Developing Countries, 1980–2012 (Absolute Values and Share of GDP) from ref. 9.

As Cheryl Payer already argued in 1974 in his book, The Debt Trap: The IMF and the Third World, this framework perpetuates dependency and structural constraints rather than enabling sustained development. Resisting this framework however has, in several cases, led to severe political destabilization or regime change, particularly where non-compliance intersected with broader geopolitical interests (1966: Nkrumah in Ghana; 1973: Allende in Chile; 1987: Sankara in Burkina Faso). If financial dependence is the primary mechanism of neocolonial control, then any serious discussion of development must eventually confront not only how this system operates, but whether meaningful alternatives to it are possible.

Ghana Under Structural Adjustment

Despite their stated objective of economic stabilization, the adoption of IMF and World Bank programs in Ghana following the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah did not produce stability. Instead, the country entered a prolonged period of reform attempts, recurring military coups, and deepening economic crisis. In this period, real wages declined by approximately 80%, average annual inflation exceeded 50%, food production fell by roughly 30%, food imports tripled, and export revenues declined by about 50%. By 1983, Ghana’s economy had effectively collapsed, and the government once again turned to the International Monetary Fund. [12]

In the following years, Ghana experienced rising export earnings in primary commodities, particularly gold and cocoa. In parallel public spending on education and health was substantially reduced from approximately 10 to 1.3% of government expenditure. [12] But despite reported GDP growth rates of 5–7%, poverty increased and income inequality widened, as reflected in a rising Gini coefficient, indicating that economic gains were unevenly distributed. [13] This outcome reflected the narrow export base of the economy, which remained heavily dependent on gold and cocoa, leaving fiscal revenues highly vulnerable to fluctuations in world market prices. Periods of high commodity prices generated temporary growth, but these episodes did not translate into broad-based or durable improvements in living standards.

As macroeconomic stabilization was achieved in the 1990s, Ghana was presented as a “model case” of structural adjustment, but its reliance on foreign borrowing and commodity exports persisted.[14] It is noteworthy that, despite large-scale mining operations, the share of generated value retained within Ghana has remained low. During the 1990s, gold extracted in Ghana was valued at approximately 5.2 billion USD, yet only about 80 million USD, roughly 2%,[15] remained in the country, with the vast majority of profits transferred abroad. A similar pattern persists today: in 2021, gold production worth around USD 5 billion generated only about 25 million USD in domestic investment, equivalent to approximately 0.5%, [16] underscoring that most of the generated value of Ghana’s mineral wealth left the country.

Environmental and Social Costs

What is far harder to quantify are the environmental and social costs remaining in the country. Gold is often perceived as a clean and pure substance, yet the reality of gold mining can be horribly destructive. Gold mining has one of the largest land-use footprints of all extractive activities, second only to coal,[17] and relies on toxic chemicals such as cyanides or mercury. [18] Artisanal and small-scale gold mining often relies on mercury-based amalgamation, releasing roughly one kilogram of mercury per kilogram of gold [19] and accounting for about one third of global mercury emissions.[20] Mercury is highly persistent, can remain in water for centuries, bioaccumulates in fish and crops, and causes severe long-term health effects, including neurological damage.

As a result, gold mining in Ghana has led to extensive deforestation, severe environmental degradation, and significant public health impacts.[21] Large river systems have been transformed into heavily polluted and toxic waterways contaminated with mercury and cyanide. WaterAid is calling for “immediate action to end the ecocide caused by illegal mining” following reports that the Ghana Water Company has been forced to reduce its clean water supply by 75%, impacting hundreds of thousands of residents across the southern coast of the country.[22] According to Ghana’s Water Resources Commission, continued degradation could force the country to import drinking water as early as 2030. [23]

In summary, although formal colonial rule ended, Ghana’s political independence did not yield economic autonomy. Its dependence on foreign loans and compliance with structural adjustment programs continue to set the economy towards debt servicing and the export of primary commodities to industrial countries. As a result, economic diversification was hindered and much of the value generated accrued abroad, reproducing the extractive logic of colonial rule. The former Gold Coast colony exemplifies the natural resource curse, with gold extraction generating revenues that flow abroad while the environmental costs of mining stay. Over time, this “gold curse” has contributed to the deterioration of basic living conditions, including access to clean water.

Debt, Dollar, and Dependence

But as the economist James A. Robinson concludes, it is not natural resources themselves that determine outcomes, but whether the governing institutions are inclusive or extractive. While Venezuela’s oil-driven economy and Ghana’s gold dependency coincide with the decline of its domestic economies, Norway’s management of oil revenues [24] and Botswana’s use of diamond wealth [25] demonstrate that inclusive institutions can transform natural resources into long-term prosperity. Norway channels oil revenues into a transparent sovereign wealth fund governed by strict fiscal rules, ensuring long-term stability, while Botswana combined relatively strong rule of law, low corruption, and effective state participation in the diamond sector to reinvest revenues into public goods. Norway never relied on IMF or World Bank lending and avoided structural adjustment entirely, while Botswana used limited World Bank financing but largely avoided IMF programs, retaining policy autonomy and institutional control.

Natural resources are therefore neither destiny nor curse: it is the institutional handling of them that determines whether they undermine or enhance economic development. Countries tied into IMF and World Bank lending frameworks, see their resource revenues prioritized for debt payments rather than domestic investment, reinforcing long-term fiscal dependence. In 2025, 47 countries are paying more than 50% of their budget to debt servicing. [26] Across the global South debt servicing is absorbing 45% of government revenue, worse than in 2024 and the worst since records began. This share exceeds total spending on education, health and social protection combined by 20%. [26] This neocolonial dependence works via perpetual debt and is sustained by the elasticity of the dollar-based fiat regime. Creditors face limited default risk because new loans can always be extended, deepening dependency of the developing countries. This arrangement insulates creditors from default risk and generates a form of institutionalized moral hazard, in which lenders can continue extending credit without bearing the full consequences of insolvency.

Perpetual Debt and Exit Options

Historically, this would not have been possible under a hard money regime such as the gold standard. Because money creation and credit expansion were constrained by finite gold reserves and convertibility requirements. Neither creditors nor debtors could sustain imbalances indefinitely. Persistent refinancing of insolvent positions would have led to reserve depletion, illustrated by the erosion of US gold reserves during the Vietnam War, the surge in foreign claims on gold, and the suspension of gold convertibility under the Nixon administration in 1971. In contrast, the current fiat monetary system permits continuous balance-sheet expansion and debt rollover, enabling external indebtedness and net capital outflows from developing countries to persist for decades and reach unprecedented, trillion-dollar scales without resolution.

If financial dependence is the primary mechanism of neocolonial control, then any serious discussion of development must eventually confront not only how this system operates, but whether meaningful alternatives to it are possible. From this perspective, Bitcoin introduces a qualitatively different monetary option into the discussion. As an independent, supply-capped monetary system, it resembles a hard money standard in that it eliminates discretionary credit expansion and limits the ability to refinance insolvency through monetary issuance. In theory, widespread use of such a system would reintroduce binding financial discipline, making long-term debt rollover without real adjustment structurally difficult. While Bitcoin does not resolve underlying trade dependencies, it offers a different monetary rule, restricting the mechanisms that currently enable institutionalized debt dependency and creditor moral hazard.

Bitcoin as a Complementary Strategy

While a transition to a global Bitcoin-based monetary standard seems unlikely in the foreseeable future, given the central role of sovereign national currencies for national fiscal budgets, the use of Bitcoin at smaller scales can nevertheless represent a rational strategy.

-

At the individual level, Bitcoin’s capacity to preserve value in a supply-capped, non-state monetary asset offers a meaningful expansion of financial agency. Because it is neutral, borderless, and independent of domestic currency regimes. Bitcoin allows individuals to store and transfer value without exposure to local inflation or political interference. This feature is particularly valuable in developing countries, where personal wealth is often tightly bound to the stability of the national currency. And as countries with lower income levels are more likely to experience large depreciation. [27] Bitcoin partially decouples individual financial security from external vulnerabilities.

-

At the Government level, Bitcoin can function as a complementary instrument for reducing exposure to institutionalized debt dependency. By monetizing otherwise stranded or excess energy, such as hydropower, geothermal, or curtailed renewable generation, governments can convert domestic resources directly into a globally liquid asset without intermediaries or conditional financing. Unlike commodity exports, Bitcoin mining does not require market access concessions or meeting procurement conditions, thereby offering a pathway to generate revenue and accumulate reserves outside the traditional creditor framework.

Implications for Policy and Development Practice

Bitcoin is the first globally accessible monetary network that allows energy-rich but capital-poor countries to convert local abundance into monetary independence. The experience of Bhutan demonstrates feasibility. By mining Bitcoin with surplus hydropower, the country accumulated reserves equivalent to 30% of their GDP, [28] which were partially used to stabilize public finances during a liquidity crisis. Pakistan has announced similar ambitions.

Bitcoin does not reform the existing system; it offers other options. This distinction matters. Historical evidence suggests that appeals for fairer treatment within extractive structures rarely succeed. Opting out, by contrast, offers a path to reduced dependence.[29] Or as Richard Buckminster Fuller put it: “To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” The question is no longer whether alternative options are possible, but whether they will be used at scale.

This analysis suggests that export expansion that deepens external indebtedness should be treated as warning signals rather than successes. NGO leaders and policymakers in countries with high sustainable energy potential should assess energy build-out and the feasibility of converting excess energy into liquid financial reserves to increase monetary autonomy.

References

- Sachs, J.D., Warner, A.M. The curse of natural resources. Eur Econ Rev 45, 827–838 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(01)00125-8

- Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (London: Thomas Nelson, 1965)

- https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v24/d237

- https://www.nytimes.com/1978/05/09/archives/cia-said-to-have-aided-plotters-who-overthrew-nkrumah-in-ghana.html

- https://www.reuters.com/markets/developing-countries-record-14-trillion-debt-service-bill-squeezes-budgets-2024-12-03

- https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/overview

- https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7c93bf40f0b626628ad097/German_Ext_Debts_Pt_1.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2011/sep/07/aid-benefits-donor-countries-companies

- Financial Flows and Tax Havens: Combining to Limit the Lives of Billions of People., Centre for Applied Research at the Norwegian School of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Instituto de Estudos Socioeconômicos, and Nigerian Institute of Social and Economic Research, December 2015. https://gfintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Financial_Flows-final.pdf

- Hickel, J., Sullivan, D., & Zoomkawala, H. (2021). Plunder in the Post-Colonial Era: Quantifying Drain from the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1960–2018. New Political Economy, 26(6), 1030–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2021.1899153

- https://www.cgdev.org/blog/aid-reverse-facts-or-fantasy

- Graham, Y. (1988). Ghana: the IMF’s African success story? Race & Class, 29(3), 41-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/030639688802900303

- https://fred.stlouisfed.org/data/SIPOVGINIGHA

- https://www.imf.org/en/countries/gha/ghana-lending-case-study

- https://therealnews.com/ghanas-unions-and-left-reject-bailout-talks-with-the-imf-as-economic-crisis-spirals

- https://pulitzercenter.org/stories/neocolonialism-and-suppression-ghanas-gold-sector

- Tang, L., Werner, T.T. Global mining footprint mapped from high-resolution satellite imagery. Commun Earth Environ 4, 134 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00805-6

- Müezzinoglu, A. (2003). A Review of Environmental Considerations on Gold Mining and Production. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 33(1), 45–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643380390814451

- Korte, Friedhelm and Frederick Coulston. “Some Considerations on the Impact on Ecological Chemical Principles in Practice with Emphasis on Gold Mining and Cyanide.” Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, vol. 41, no. 2, 1998, pp. 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1006/eesa.1998.1692

- https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/global-mercury-assessment-2018

- https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cn9dn8xq92jo

- https://www.wateraid.org/gh/blog/wateraid-demands-immediate-halt-to-illegal-mining-as-water-supply-drops-75-due-to-pollution

- https://issafrica.org/iss-today/ghana-must-stop-galamsey-before-it-sinks-the-country

- https://www.nbim.no/en/about-us/about-the-fund/

- https://issafrica.org/iss-today/botswana-has-valued-good-governance-as-much-as-diamonds

- https://www.development-finance.org/en/news/873-washington-debt-service-watch-2025-briefing-and-database-released

- Culiuc, A., & Park, H. (2025). Currency Crises in the Post-Bretton Woods Era: A New Dataset of Large Depreciations (IMF Working Paper No. 2025/221). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9798229027793.001

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Bhutan

- Gladstein, A. (2025). Why Bitcoin is freedom money. Journal of Democracy, 36(4), 20–35.